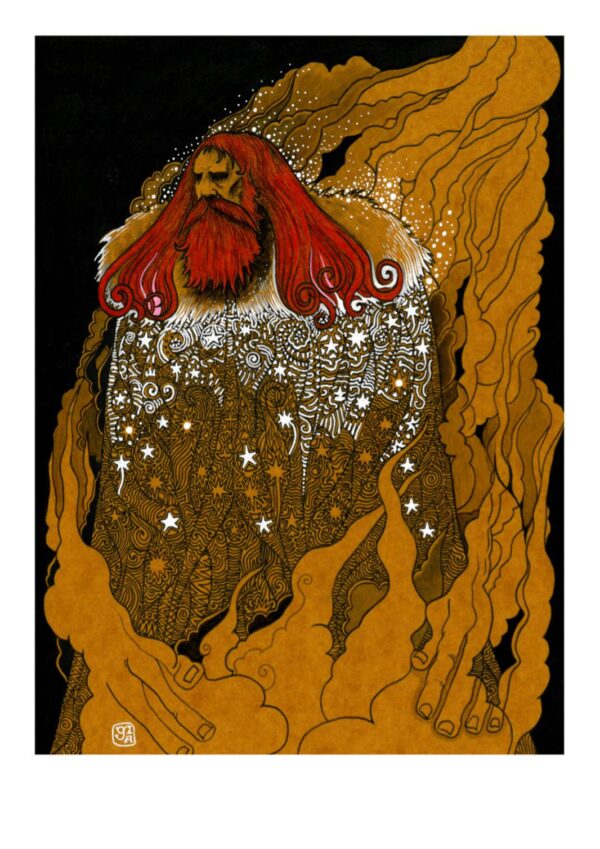

Description

The Dagda in Ancient Irish Mythology

Print edition

A4 11.7 x 8.3 inches

Signed by the artist

In the mist-shrouded landscape of Irish mythology, where deities embody the raw forces of nature and culture, one figure stands as a colossal pillar of contradiction and complexity: the Dagda. Known as An Dagda Eochaid Ollathair—”the Good God, All-Father”—he is a figure of immense power and disarming simplicity, a ruler of the gods who is also a figure of ribald humour. He is the master of life and death, a warrior and a sage, a provider and a prodigious consumer. To examine the Dagda is to delve into the deepest structures of the pre-Christian Irish worldview, where sovereignty, magic, and the mundane necessities of life intertwine. He is not a distant, omniscient sky father but an earthy, engaged, and deeply relatable patriarch whose stories encode the fundamental values and anxieties of the society that venerated him. His character represents a unique fusion of brute strength, benevolent provision, and potent magic, making him the ultimate symbol of effective and legitimate kingship.

The Dagda’s primary role is as the chieftain of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the People of the Goddess Danu, during their climactic conflict with the monstrous Fomorians. His very name is a title, and its meaning—”the Good God”—is multifaceted. It does not signify moral perfection in a modern sense but rather denotes proficiency, excellence, and ultimate efficacy. He is “good” at everything he does. He is the good warrior, the good provider, the good magician. He is also called Eochaid Ollathair, “Horseman, All-Father,” emphasizing his paternal, protective relationship to the tribe and his connection to the horse, a potent symbol of sovereignty and power in Celtic culture. From the outset, he is positioned as the foundational father figure of the divine race.

This identity is powerfully expressed through his three great treasures, each an extension of his essential functions as a sovereign. The first is his mighty club, or lorg mór, which is so immense it had to be dragged on wheels. This weapon possesses two awesome functions: one end can kill the living with a single blow, while the other end can restore the dead to life. This club encapsulates the Dagda’s role as the master of the cycle of life and death. He is not merely a destroyer; he is a restorer, a god whose power encompasses both the battlefield and the regeneration of his people. It is the ultimate instrument of a king’s justice and mercy.

His second treasure is the coire ansic, the Undry Cauldron. Unlike the later, more mystical Grail, the Dagda’s cauldron is a profoundly practical and social object. It is a bottomless source of nourishment from which no company ever goes away unsatisfied. This cauldron is the heart of the ideal of kingship: fír flathemon, the “ruler’s truth.” A true king ensures that the land is fertile and his people are fed. The Dagda, through his cauldron, is the ultimate fulfiller of this contract. He is the provider of abundance, the guarantee against famine, and the centre around which the community gathers in security and plenty. His power is not abstract; it is measured in full stomachs and communal feasts.

The third treasure is his magical harp, the uaithne. This is not merely an instrument for entertainment. In a culture where the bard held immense power, the harp is an instrument of order. It can play three sacred types of music: goltraí (lamentation), which makes its listeners weep; geantraí (joyous music), which makes them laugh; and suantraí (sleep music), which lulls them into slumber. When the Fomorians steal the harp after the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, the Dagda journeys with Lugh and Ogma to reclaim it. He does not fight his way in; he calls the harp to him, and it flies to his hand, killing nine men along the way. He then plays the three strains, reducing the Fomorian warriors to tears, then laughter, and finally a profound sleep, allowing the gods to escape easily. This episode demonstrates that the Dagda’s power is also the power of glám dícenn (satire) and sacred art—the power to orchestrate emotion and impose social and emotional order upon chaos.

However, the Dagda’s character is defined as much by his gargantuan appetites as by his mighty weapons. He is a profoundly physical and earthy god, a quality that prevents him from becoming a remote, Olympian figure. The most famous story that illustrates this is his encounter with the Fomorian king, Bres, who seeks to humiliate him by imposing a seemingly impossible task. He commands the Dagda to eat a prodigious amount of porridge—a gruel made with eighty gallons of milk, whole goats, sheep, and pigs, all poured into a vast pit. The Dagda not only consumes the entire mess with a gigantic spoon but also scrapes the bottom and sides of the pit, leaving great furrows in the earth. Afterwards, so bloated that his stomach hangs near the ground, he drags himself away and has sex with a Fomorian princess who mocks his appearance.

This bizarre and comical episode is far from mere crude humour. It is a rich mythological statement. Firstly, it is a test of sovereignty. The ability to consume the land’s produce is the inverse of the ability to provide it. By devouring the gigantic meal, the Dagda demonstrates his mastery over the very substance of provision; he is the ultimate consumer because he is the ultimate provider. His distended belly is not a sign of gluttony but a symbol of his capacity to incorporate and transform the bounty of the world. Secondly, his sexual union immediately afterwards reinforces his role as a god of fertility and life force. Even in a state of apparent vulnerability and ridicule, his generative power is undiminished. The Fomorians, representing blight, sterility, and chaos, seek to humiliate him through excess, but they fail. The Dagda’s appetites are a fundamental part of his power; he is the embodiment of a successful and fertile land, and his vast consumption is a necessary part of that cycle.

The Dagda’s role reaches its apex in the Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Mag Tuired), the epic conflict where the ordered, skilled, and cultured Tuatha Dé Danann face the chaotic, oppressive, and grotesque Fomorians. Here, the Dagda operates as both a strategist and a primal force. On the eve of the battle, he is sent by Lugh, the young champion, on a mission to the Fomorian camp to delay their attack. This results in the famous scene of the Dagda’s porridge-eating, but it is also a act of espionage. While there, he sees the Fomorian princess and later mates with her, an act that can be interpreted as a magical rite to ensure the fertility and victory of his own people—a symbolic impregnation of the future.

Most crucially, the Dagda is the one who single-handedly secures the victory. While Lugh fights the Fomorian king Balor and slays him with his sling, the narrative makes it clear that the battle is won by the Dagda’s earlier actions. As the Fomorian army flees, the Dagda uses his great club to wreak havoc, harvesting the enemy like a farmer reaping wheat. His weapon, which kills and resurrects, is here used to its full destructive potential, mowing down the forces of sterility to clear the way for a new age of prosperity under the Tuatha Dé. He is the indispensable, foundational power upon which the more glamorous heroics of Lugh depend.

Despite his immense power, the Dagda is not portrayed as infallible or always dignified. His relationship with the Morrígan, the terrifying goddess of war and sovereignty, is particularly telling. On the eve of the battle, he encounters her washing the clothes and armour of those destined to die—a classic phantom queen motif. They have intercourse there by the river, and through this union, she pledges to use her own formidable power to destroy the Fomorian king Indech, thus ensuring victory. This encounter frames sovereignty not as a solitary male achievement but as a partnership with a fierce, feminine force. The land itself, in the form of the Morrígan, must be wooed and satisfied for kingship to be legitimate and victorious.

Furthermore, the Dagda’s status as “All-Father” is complicated by his numerous children, who are among the most prominent figures of the Tuatha Dé Danann. His daughter is Bríg, the goddess of poetry, healing, and smithcraft, associated with the later Saint Brigid. His sons include the lovesick Midir of Brí Léith and the heroic Aengus Óg, the god of youth, whom the Dagda famously conceives and births in a single day to circumvent a legalistic promise. These offspring show the Dagda’s generative power extending into the domains of art, love, and youth, proving that his influence is the foundational thread from which the entire tapestry of the Tuatha Dé is woven.

In conclusion, the Dagda is the architectural cornerstone of the Irish mythological system. He is a god of profound contradictions: a king who appears as a rustic oaf, a warrior whose greatest weapon also heals, a father-god whose power is expressed through colossal consumption and sexuality. He embodies the essential qualities of ideal kingship: the strength to protect, the magic to ensure order, and the abundance to provide. His stories, oscillating between the epic and the ribald, the sacred and the profane, reflect a worldview where power was not abstract but tangible, located in the full cauldron, the fertile field, and the victorious tribe. He is not a distant sky-god but an earthy, immanent force. The Dagda is, in the truest sense, the “Good God”—the effective, proficient, and ultimate master of the world he protects and provides for, a testament to the Celtic understanding that true power lies in the harmonious balance of force, wisdom, and unashamed vitality.

Parsifal. Original artwork

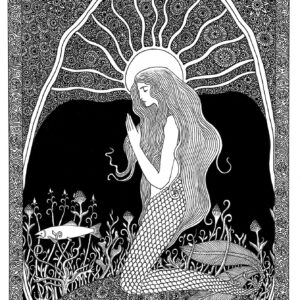

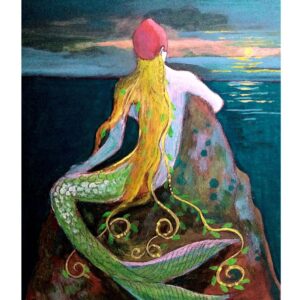

Parsifal. Original artwork  The Merrow in Irish Folklore and History.

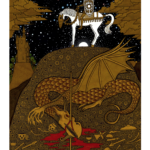

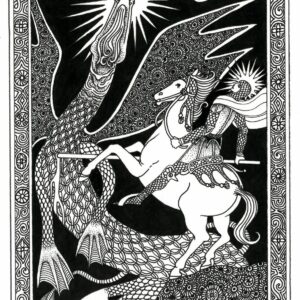

The Merrow in Irish Folklore and History.  Saint George and the Dragon. Fine art print.

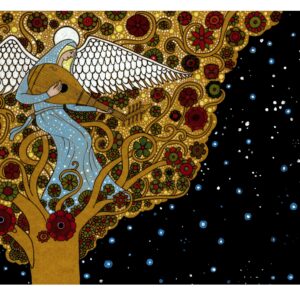

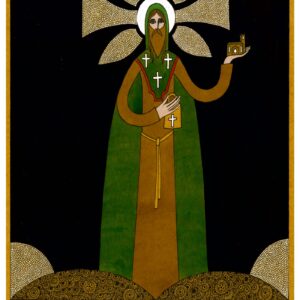

Saint George and the Dragon. Fine art print.  Saint Brigid. Fine art print. Early Irish Saint

Saint Brigid. Fine art print. Early Irish Saint  Sacred feminine flame print edition.

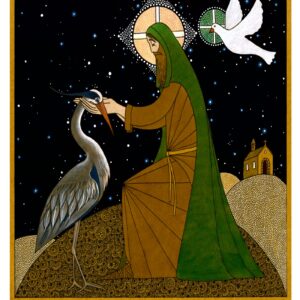

Sacred feminine flame print edition.  Saint Ita. Fine art print.

Saint Ita. Fine art print.