Description

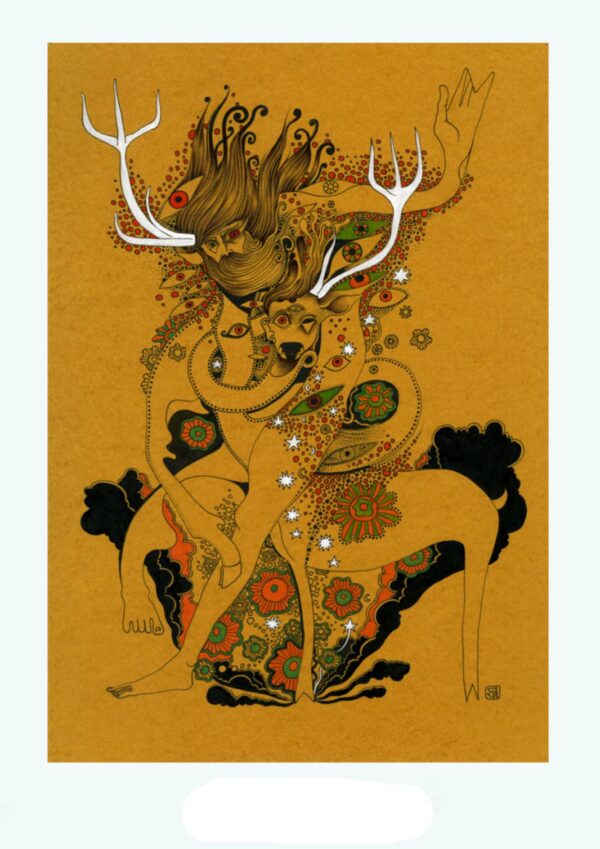

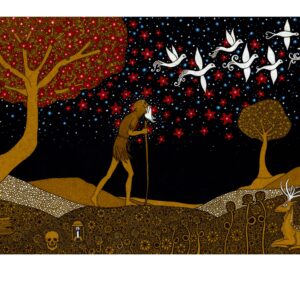

The Ancient Shape-Shifter: Tuan mac Cairill and the Deer of Irish Mytho-History

A4 print. 11.3 x 1.7 inches

Signed by the artist

In the vast and intricate tapestry of Irish mythology, where gods stride across the landscape and heroes commit impossible feats, one figure stands apart not for his martial prowess or destructive power, but for his profound, lonely endurance. He is Tuan mac Cairill, the sole repository of Ireland’s primal history, a chronicler who did not learn his tales from scrolls but lived them through a succession of animal forms. His story, central to the text known as The Testament of the Ancient Men or Scéla Tuáin meic Chairill, is a unique and powerful narrative of transmigration, memory, and identity. Tuan’s specific transformation into a deer is not merely a fantastical episode; it is a critical juncture in a symbolic journey that encapsulates the Celtic understanding of the soul’s journey, the deep connection between humanity and nature, and the very mechanism by which pre-Christian history was preserved and transmitted in a Christian era. To examine Tuan’s life as a deer is to peer into the soul of early Irish literature itself.

The story of Tuan comes to us from the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions), the grand pseudo-history that weaves together myth, legend, and biblical genealogy to explain the peopling of Ireland. Tuan’s account is presented as the firsthand testimony of the sole survivor of the first invasion, that of Partholón. He tells his story to St. Finnian of Moville in the 6th century, creating a direct, albeit miraculous, bridge between the pagan past and the Christian present. Tuan recounts how he alone survived a great plague that wiped out his people. As the ages passed and new waves of invaders—the Nemedians, the Fir Bolg, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and finally the Milesians—came to Ireland, Tuan did not merely live on. Instead, he underwent a series of remarkable transformations, ageing and then rejuvenating by entering a sacred sleep and awakening in a new bodily form. His journey through time is a journey through the animal kingdom: he becomes a stag, a wild boar, a hawk, and finally a salmon. Each form corresponds to a new era of Irish history, allowing him to witness the entirety of the island’s foundational epochs.

The transformation into a deer is Tuan’s first and perhaps most symbolically resonant metamorphosis. After the extinction of the Partholónians, he grows old and feeble, a lone human relic in an empty land. He enters his regenerative sleep and awakens as a mighty, antlered stag (dam allaid in Old Irish). In this form, he becomes the “lord of herds” over all the wild deer of Ireland. This is a critical detail. He does not become just any deer, but their king. This establishes a pattern where Tuan’s essential consciousness—his ego and memory—is not diminished by his change of form but is rather enhanced by it, assuming a position of nobility and authority within the new natural order. As a stag, he witnesses the arrival of the next wave of invaders, the Nemedians, and observes their struggles from the deep woods, a silent, antlered chronicler of their triumphs and failures.

The choice of a stag as his first animal form is profoundly significant within a Celtic context. The deer was not merely a common animal; it was a sacred creature, imbued with potent symbolic meaning. In Celtic iconography and myth across Europe, the stag is consistently associated with sovereignty, fertility, and the Otherworld. It is an animal of the forest, a liminal space that exists between the settled world of humans and the wild, unknown realm of the gods. Cernunnos, the “horned god,” is a pan-Celtic deity often depicted cross-legged with antlers or holding a torc and a serpent, master of animals and a symbol of regenerative power. Tuan’s assumption of the stag form connects him directly to this ancient archetype. He becomes a embodiment of the wild, untamed spirit of Ireland itself, a guardian of the land’s deep memory long before any human kingdom was established.

Furthermore, the stag is a powerful symbol of cyclical renewal. The annual shedding and regrowth of its antlers made it a natural symbol of death and rebirth, of the endless cycle of the seasons. This makes it the perfect vessel for Tuan, whose entire existence is defined by cyclical renewal. Just as the stag loses its antlers to grow new, larger ones, Tuan sheds his aged human body to be reborn into a stronger, more vital form. His life as a stag is a life in harmony with these natural cycles; he rules the herds through seasons of abundance and scarcity, mirroring the rise and fall of the human populations he observes from a distance.

The narrative purpose of Tuan’s cervine existence extends beyond powerful symbolism. It establishes the method of his unique historiography. As a deer, he is an ideal witness. He is close enough to human activity to observe it—watching the Nemedians from the edge of the forest—but remains fundamentally separate from it. He is not a participant in their wars or politics; he is a pure observer, untainted by partisan bias. His perspective is that of the natural world itself, watching the comings and goings of humanity with a detached, ancient eye. This lends his subsequent testimony a unique authority. His history is not a king’s boast or a bard’s flattery; it is the objective record of the land, recounted by a consciousness that has become one with the wild soul of Ireland.

This theme of the “wild witness” is crucial. Tuan’s story represents a deep-seated Celtic belief in the natural world as a conscious, sentient repository of memory. The stones, the trees, and the animals have witnessed all of history. Tuan’s transformations are a narrative device that personifies this belief. He becomes the memory of the landscape. His time as a stag, the first and most noble of his animal forms, sets this precedent. The woods and the creatures within them are not just a backdrop for human history; they are its silent, remembering witnesses.

Tuan’s journey continues. After his long life as the lord of deer, he ages again and transforms into a wild boar, another animal laden with martial and royal symbolism in Celtic culture. Later, he becomes a hawk, gaining the freedom of the skies and a sweeping, panoramic view of the events below. Finally, he becomes a salmon, the ultimate symbol of wisdom in Irish myth. In this piscine form, he is caught and eaten by the wife of Cairill, a chieftain, thus leading to his rebirth as a human, Tuan mac Cairill (Tuan, son of Cairill). This rebirth is the culmination of his journey. The wisdom and knowledge he consumed throughout his animal existences—particularly as the salmon of knowledge—are now housed once more in a human body, ready to be spoken.

This final transformation is key to understanding the story’s function in a Christian monastic context. The Irish monks who recorded this myth were grappling with a problem: how to preserve the history and lore of their pagan past within a Christian worldview. Tuan’s story provides a miraculous, theologically acceptable solution. His prolonged life is not presented as demonic or necromantic but as a God-given miracle that allowed for the preservation of knowledge. St. Finnian, upon hearing Tuan’s story, does not decry it as heresy but venerates it as a divine mystery. Tuan becomes the perfect source: a pre-Christian witness whose testimony has been delivered, through a series of wondrous events, into the hands of Christian scholarship. The animal transformations, beginning with the stag, are the mechanism that makes this transmission possible, grounding the incredible history in the familiar, respected imagery of the natural world.

When we focus on Tuan’s existence as a deer, we see the foundational layer of this entire process. The stag is the first step in his journey away from humanity and towards a complete identification with the natural world. It is in this form that he first perfects his role as the observer. The dignity and sovereignty associated with the stag lend authority to his subsequent testimony. He is not a mere beast; he was a king of beasts, and his account carries that weight.

In conclusion, Tuan mac Cairill’s transmutation into a deer is far more than a whimsical metamorphosis. It is a deeply considered narrative choice rooted in Celtic symbolism, cosmological belief, and the pragmatic needs of historical preservation. As a stag, Tuan embodies the sacredness of the wild, the cyclical nature of time, and the sovereignty of the land itself. This form allows him to become the ideal witness to history: objective, noble, and eternally present. His entire story, culminating in his rebirth as a human storyteller, serves to bridge the chasm between pagan Ireland and Christian Ireland, between the oral tradition of the druids and the written tradition of the monks. Through the figure of the ancient stag-king watching from the oak groves, Irish mythology asserts a profound truth: that the land itself remembers, and that the deepest history is not found in books, but in the wild, remembered by those who have become one with it. Tuan’s story is the ultimate expression of the Celtic reverence for nature, not as a resource to be used, but as a conscious, living chronicle of all that has ever been.

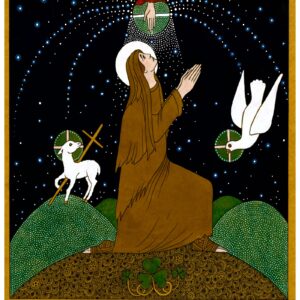

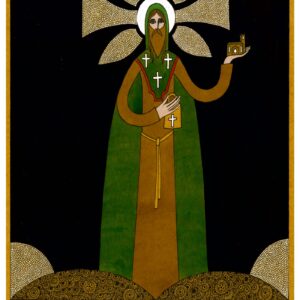

Saint Ninnidh. Fine art print.

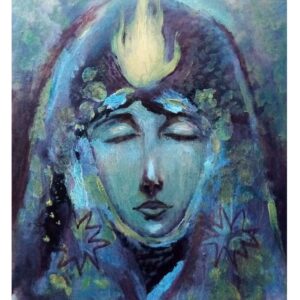

Saint Ninnidh. Fine art print.  Sacred feminine flame print edition.

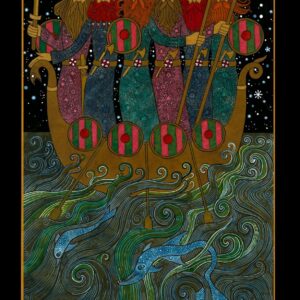

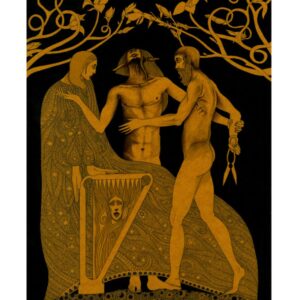

Sacred feminine flame print edition.  King Labhraidh Loingseach. The King with Horse’s Ears. print edition

King Labhraidh Loingseach. The King with Horse’s Ears. print edition