Description

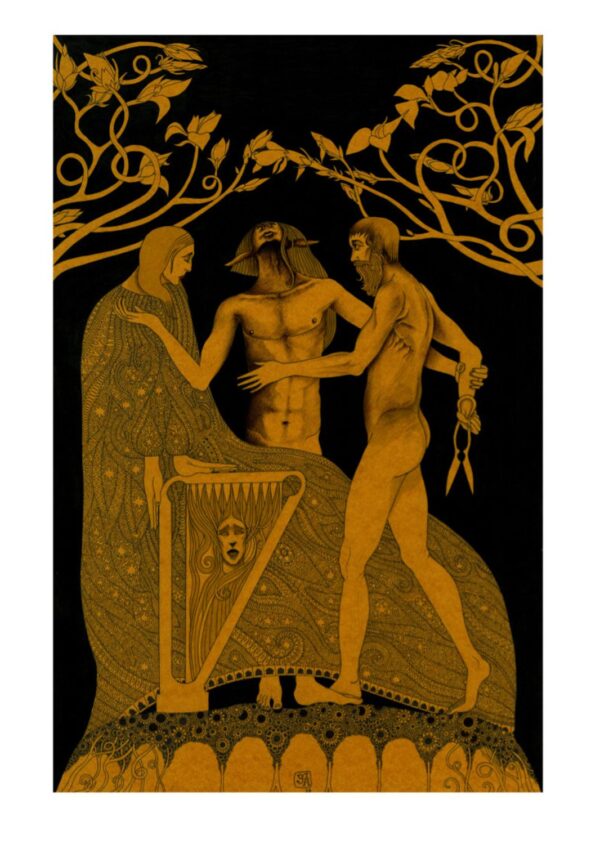

King Labhraidh Loingseach: The King with Horse’s Ears and the Echoes of Sovereignty

Print edition.

A4 11.3 x 8.7 inches

Signed by the artist

In the rich tapestry of Irish mythology, certain figures stand out not for their flawless heroism, but for their complex humanity, their flaws, and the profound cultural truths their stories encode. Among these is Labhraidh Loingseach, a legendary King of Leinster and High King of Ireland, whose name is forever linked to one of the most enduring and psychologically resonant motifs in world folklore: the secret of the king with animal ears. While versions of this tale exist across cultures, from the Greek myth of King Midas to the Welsh narrative of March ap Meirchion, the Irish story of Labhraidh Loingseach is uniquely woven into the fabric of pseudo-historical tradition, exploring themes of kingship, shame, truth, and the inescapable nature of destiny. His story is more than a simple folktale; it is a deep meditation on the burdens of power and the price of authenticity.

Labhraidh’s story is preserved in several key texts, including the Metrical Dindshenchas (lore of places), the Book of Leinster, and later folk traditions. His narrative is twofold: first, the epic saga of his exile and return, which fits the classic “returning heir” archetype; and second, the more intimate and peculiar drama of his equine deformity and its consequences. To understand the man with horse’s ears, one must first understand the king who won a throne.

Part I: The Exile and the Return – Labhraidh the Warrior King

Labhraidh’s early life is a tale of usurpation and vengeance. His grandfather, Lóegaire Lorc, was a High King murdered by his own brother, Cobthach Cóel Breg of Brega, a man so consumed by jealousy he was said to have been “wasted to a skeleton” – hence the epithet Cóel (the slender). Cobthach’s treachery knew no bounds; he forced Lóegaire’s son, Ailill Áine, to consume his own father’s heart. Ailill, in his shame and grief, died of thirst, a fitting end for one who had been forced to ingest the source of life and courage.

This left Ailill’s son, Labhraidh, as the last rightful heir. Fearing the boy’s vengeance, Cobthach had him sent into exile overseas. The name Loingseach means “the Exile” or “the Mariner,” denoting this period of his life. Labhraidh found refuge in Munster and later, significantly, in Gaul. This exile is a crucial component of the Irish hero’s journey; like Lug Lámhfada or the sons of Uisneach, time abroad is a period of maturation, skill acquisition, and alliance-building. In Gaul, Labhraidh became a renowned mercenary, earning the fierce loyalty of a troop of Gaulish warriors (na Fianna Gall). This foreign army would become the instrument of his redemption.

With his band of loyal Gauls, Labhraidh returned to Ireland to reclaim his birthright. His rise was strategic and brutal. He first secured the patronage of the King of Munster, Scoriath, by marrying his daughter, Moriath. Their courtship itself is a sub-tale of cunning and magic, involving a love potion brewed by the harper Craiftine, whose music could sway emotion. With Scoriath’s support and his Gaulish fianna, Labhraidh marched on Leinster and then on Cobthach himself.

His victory was sealed by a famous act of gruesome cunning. He invited the now-aged Cobthach to a feast in a specially built iron house. Once Cobthach and his retinue were inside, Labhraidh’s men barricaded the doors and heated the house with fires until all within were suffocated and burned. This brutal method of regicide, which also appears in the saga of the destruction of Dá Derga’s Hostel, is a dark reflection of the Celtic imperative of sovereignty. The land itself must be purified of a corrupt and sinful king; his death is not a clean execution but a sacrificial cleansing by the elements of fire and iron. With Cobthach dead, Labhraidh Loingseach became the High King of Ireland.

Part II: The Secret and the Burden – The Mark of the King

It is at the zenith of his power that the story takes its strange and intimate turn. Despite his prowess as a warrior and a ruler, Labhraidh harboured a deep, shameful secret: he had the ears of a horse (cluasa capaill). This deformity was meticulously hidden from all his subjects. He wore his hair long to cover them, and only his personal barber was ever allowed to see them. Each barber, after performing his duty, was sworn to secrecy on pain of death.

The king’s secret became a heavy burden. The knowledge of his deformity was a corrosive truth that, if revealed, threatened to undermine his authority and transform him from a mighty sovereign into an object of ridicule. The barbers, each in their turn, could not bear the psychological weight of the secret. They would burst with the knowledge of it, telling a reed in a marsh or a tree in a forest. But a human could not contain it, and so Labhraidh, in his fear and shame, had each one put to death. This cycle of violence and silence presents a stark contrast to the victorious king of the first part of the tale. Here is a ruler so insecure in his own body, so fearful of his people’s perception, that he becomes a tyrant, killing to maintain a façade.

This pattern continued until one barber, a young boy, was chosen for the task. His mother, a widow, pleaded with the king to spare her only son. Moved by her tears, Labhraidh relented, sparing the boy’s life on the condition of absolute secrecy. The boy, however, suffered just as his predecessors had. He fell into a deep sickness, consumed by the secret he dared not speak. A wise druid, perceiving his ailment, prescribed a cure: the boy must go to a remote crossroads and whisper the secret to the first tree he saw. This act of confession, even to an unhearing entity, would lift the psychological burden.

The boy did as he was told. He went to a lonely place and whispered into the earth, “King Labhraidh has horse’s ears.” He immediately felt relief and returned to health. The secret was out, yet contained.

But the story does not end there. Some time later, the king’s harper, Craiftine (the same one who aided in his courtship), broke his cruit (a small harp). Needing wood for a new one, he went to the same crossroads and cut down the very willow tree that had absorbed the barber’s secret. He fashioned a magnificent new harp from its wood. When he was next called to play for the king and his court, he began his recitation. But as he plucked the strings, the harp did not sing a heroic ballad or a lament; instead, it sang out, in a clear, musical voice, “Labhraidh Lorc has horse’s ears! Labhraidh Lorc has horse’s ears!”

The court fell silent in shock and horror. The king’s deepest shame had been proclaimed aloud by his own harper’s instrument, in front of his entire assembled nobility. This is the climax of the tale—the moment of terrifying exposure.

Part III: The Revelation and the Resolution – The Anatomy of Sovereignty

King Labhraidh’s reaction to this public humiliation is what transforms the story from a simple cautionary tale into a profound commentary on kingship. Faced with the irreversible revelation of his secret, the king had a choice: to continue his tyranny by executing the harper and the court, or to finally accept his own nature.

In a moment of supreme courage and wisdom, Labhraidh chose the latter. He stood before his people, pushed back his long hair, and revealed his equine ears. He embraced the truth of his own body. And in doing so, a miracle occurred. The assembly, seeing their king’s vulnerability and his courage, did not revolt or laugh. Instead, they cheered. They accepted him, not in spite of his difference, but because of his honesty and the strength he showed in embracing it. The secret, once a source of shame and death, became a public fact that ultimately strengthened his rule. The burden was lifted.

This resolution is deeply significant. In Celtic cosmology, the physical perfection of the king was intrinsically linked to the prosperity of the land—a concept known as fír flathemon (the ruler’s truth). A king with a blemish could cause the land to become barren and disordered. Labhraidh’s horse ears were such a blemish, a mark of Otherness that defied the ideal of royal perfection. His initial response—hiding the flaw and killing those who knew it—was a attempt to maintain this cosmic order through fear. But true fír flathemon is not about perfection; it is about integrity. By accepting and revealing his flaw, Labhraidh demonstrated a deeper, more authentic form of truth. He showed that sovereignty is not about being a flawless god-king, but about being a truthful, courageous leader. His acceptance of himself allowed the people to accept him, and thus the cosmic order was restored not through perfection, but through authenticity.

The equine imagery itself is potent. The horse was a sacred animal in Celtic culture, associated with sovereignty, warfare, fertility, and the sun god Lugh. Goddesses of sovereignty, like Macha and Épona, were intimately linked with horses. Labhraidh’s ears may not have been a deformity, but a mark of his divine right to rule—a physical connection to the powerful, instinctive, and noble nature of the horse. His shame was a misrecognition of a blessing. By hiding them, he was denying a part of his own sacred power. Only in embracing them could he become a complete and true sovereign.

Conclusion: The Echoes in the Willow

The story of King Labhraidh Loingseach endures because it operates on multiple levels. On one hand, it is a thrilling historical saga of exile, return, and vengeance, fitting neatly into the cycle of heroic myths. On another, it is a timeless psychological drama about the weight of shame, the danger of secrets, and the liberating power of truth.

The harp made from the whispering willow is a perfect symbol of this theme. It represents the idea that truth, once released into the world, cannot be contained. It will always find a voice, often in the most unexpected ways—through art, through music, through the very instruments of culture we create. The story argues that repression is a sickness, both for the individual and the body politic, and that confession and acceptance are the only path to health.

Ultimately, Labhraidh’s journey from a vengeful heir to a fearful tyrant to an accepted sovereign mirrors the journey of any leader, or indeed any person, toward self-acceptance. His horse’s ears, initially a curse, become the very mark of his uniqueness and his strength. The king is not a king despite his horse’s ears, but because of the courage he shows in revealing them. In the end, the story of Labhraidh Loingseach is not about a king who was monstrous, but about a man who learned that the only thing truly monstrous was his own fear. And in conquering that, he secured a legacy far more enduring than any won by the sword—a legacy of truth that still resonates from the strings of a harp.

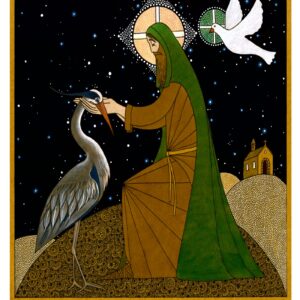

Saint Colmcille. Fine art print. Early Irish saint

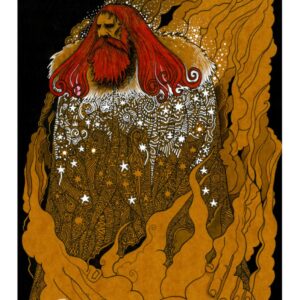

Saint Colmcille. Fine art print. Early Irish saint  The Dagda in Ancient Irish Mythology print edition

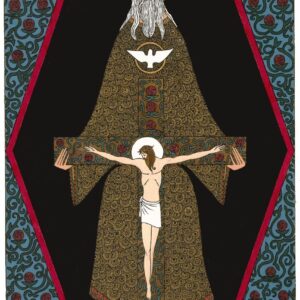

The Dagda in Ancient Irish Mythology print edition  Throne of Mercy. Fine art print.

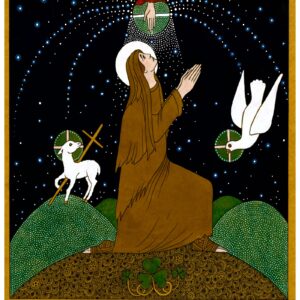

Throne of Mercy. Fine art print.  Saint Patrick. Fine art print.

Saint Patrick. Fine art print.