Description

The Merrow in Irish Folklore and History: Enchantment, Otherness, and the Lure of the Deep

Print edition.

A4 11.7 x 8.3 inches

Signed by the artist.

The coastline of Ireland, a frayed and fractured edge between the solid world of land and the mutable world of the sea, has always been a place of liminality in the Irish imagination. It is a threshold where realities blur, and where the extraordinary can, and often does, breach the mundane. From this psychogeographical space emerges one of the most captivating and complex figures in Irish folklore: the Merrow. Known in Irish as the Murúch (singular) or Murúcha (plural), these beings are Ireland’s distinct contribution to the global canon of mermaid and merman myths. Yet, to classify them merely as Irish mermaids is to overlook the profound cultural, historical, and symbolic depths they inhabit. The Merrow is a multifaceted symbol, representing the allure and terror of the sea, the potent tension between the human world and the Otherworld, and a unique, often matriarchal, strand within the Irish mythological tradition. Their stories, collected from the rocky shores of Donegal to the coves of Cork, offer a portal into the Irish psyche, reflecting a people’s relationship with the ocean that is both their lifeblood and their greatest peril.

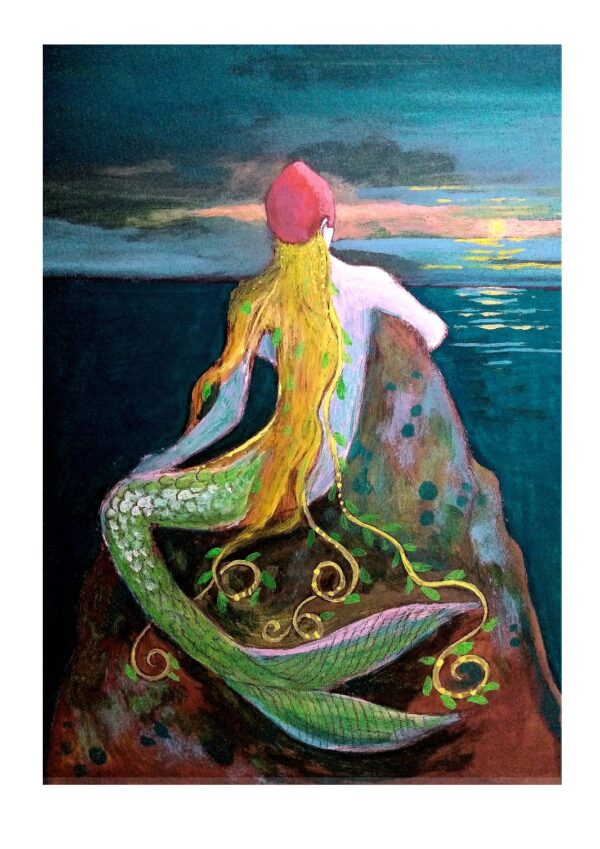

The physical appearance of the Merrow, as described in folk tales, sets them apart from their more universally recognised cousins. While sharing the classic human-fish hybrid form, the Irish Merrow is often granted specific, magical accoutrements. The female Merrow is consistently described as breathtakingly beautiful, with pale skin, long flowing hair, and eyes that hold the mystery of the deep. Their most defining feature, however, is a cohuleen driuth, a little red cap adorned with feathers, which is the source of their power to traverse the oceans. Without this cap, a Merrow is trapped on land, unable to return to her aquatic home. This cap acts as a powerful narrative device, a key to her agency and freedom, which, when stolen, becomes an instrument of her captivity.

The male Merrow, in stark contrast, is a creature of grotesque and frightening aspect. Far from the handsome triton of classical myth, he is depicted with green skin, sharp red noses, pig-like eyes, and a scaly physique. They are often described as being generally malevolent or, at best, indifferent to humans. This stark gender dichotomy is fascinating. It positions the female Merrow as the object of human desire and potential integration, a beautiful and attainable bride, while the male represents the raw, untamable, and threatening wildness of the sea itself. This gendering of the ocean—as a beautiful but dangerous feminine force that can be courted and sometimes mastered, versus a brutish, masculine force that is inherently hostile—reveals a deep-seated cultural perception of the marine environment.

The narratives surrounding the Merrow are rich and varied, but they consistently orbit themes of captivity, longing, and the irreconcilable clash between two worlds. The most common tale is the “captive wife” motif. A fisherman, enchanted by a beautiful Merrow he spies dancing on the waves or resting on a rock, steals her cohuleen driuth. Bereft of her magic, she is forced to become his wife on land. She is often a good wife, a skilled homemaker, and bears him children. Yet, a profound melancholy clings to her; she is frequently seen gazing longingly out to sea. The story’s climax arrives when, after years, she discovers her hidden cap—often revealed by a curious child—and without a moment’s hesitation, she seizes it and returns to the ocean, abandoning her human family forever. Sometimes, she may later return to watch over her children from the waves, but she is never again truly of their world.

These stories are rarely simple tales of a cruel human capturing a innocent creature. They are layered with tragedy and ambiguity. The human husband is often driven by loneliness and desire, but his act of theft is a violation that severs the Merrow from her essence. Her subsequent life on land, while comfortable, is a gilded cage. Her ultimate return to the sea is not portrayed as a betrayal but as a reclamation of her true nature. This narrative speaks powerfully to the Irish experience of the sea as a source of sustenance—fish caught, trade routes opened—but also as a place of immense, unknowable power that can never truly be owned or controlled. The Merrow wife is the spirit of the sea itself: it can be harnessed for a time, but its fundamental wildness will always reassert itself.

Beyond the domestic sphere, Merrows were also omens. Their appearance was often believed to foretell approaching storms or misfortune. Seeing a Merrow, particularly a male one, could be a harbinger of a shipwreck or a drowning. This cemented their role as liminal beings, existing at the boundary between life and death, capable of mediating between the human world and a chaotic, unpredictable natural force. In some tales, they are more benevolent, guiding lost sailors to safety or even bestowing gifts. A common motif in Kerry and Clare is that of the Merrow who comes to a household to borrow a pot or a knife and repays the kindness with an abundance of fish or with prophecies. This reflects a practical, almost neighbourly relationship with the supernatural, a hallmark of Irish folklore where the Otherworld is not always distant but can interact with daily life through established protocols of reciprocity.

To understand the Merrow’s place in Irish culture, one must situate them within the broader framework of Irish mythology and history. They are not an isolated phenomenon but part of a vast continuum of Otherworldly beings, the Aos Sí or people of the mounds. The sea was simply another dimension of this Otherworld, Tír fo Thuinn (The Land Under the Wave), a paradisiacal realm of eternal youth and beauty, akin to the more famous Tír na nÓg. The Merrow are the guardians and inhabitants of this submarine paradise. This connection is made explicit in the Fenian Cycle, where the great hero Fionn mac Cumhaill’s son, the poet Oisín, is lured to Tír na nÓg by Niamh of the Golden Hair, a figure who shares many traits with the enchanting female Merrow.

The historical context is equally crucial. For an island people, the sea was the great highway of invasion, trade, and cultural exchange, but also the source of unimaginable tragedy during the Great Famine. It was a giver and taker of life. The stories of Merrows can be read as a cultural processing of this relationship. The fear of the male Merrow embodies the terror of a storm that destroys the fishing fleet and drowns the menfolk. The captured female Merrow represents the fragile hope of mastering this environment for survival, while her inevitable escape acknowledges the ultimate supremacy of nature over human ambition. Furthermore, in a society where many men were lost at sea, the motif of the woman left behind, gazing out at the water, is powerfully mirrored by the Merrow wife’s longing for her home. The folklore provided a framework to articulate this profound sense of loss and yearning.

The collection and preservation of Merrow lore in the 19th and early 20th centuries by folklorists like Thomas Crofton Croker, Lady Augusta Gregory, and Jeremiah Curtin occurred alongside a rising Irish national consciousness. As Ireland sought to define its cultural identity distinct from Britain, its folklore was elevated from peasant superstition to a national literature. The Merrow, along with the Banshee, the Leprechaun, and the Púca, became an emblem of a unique Celtic imagination. Writers of the Irish Literary Revival, particularly W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge, wove these figures into their work, cementing their place in a romanticised, yet potent, national narrative. The Merrow was no longer just a figure of local belief but a symbol of Ireland’s mystical, pre-modern soul.

In a modern context, the Merrow has not been consigned to history. She continues to surface in contemporary Irish literature, music, and art. Authors like Paul Muldoon and Paula Meehan have drawn on the imagery of the Merrow to explore themes of exile, identity, and ecological concern. The Merrow’s story—of a being trapped between two worlds—resonates deeply in a globalised age of migration and cultural dislocation. Furthermore, in an era of climate change and rising sea levels, the Merrow takes on a new prophetic role. She is no longer just an omen of a single storm but a potent symbol of the ocean itself, which humanity has plundered and polluted, and which may now be rising to reclaim its dominion. Her warning calls, once heard only by fishermen, now feel directed at all of civilisation.

In conclusion, the Merrow of Irish folklore is a figure of astonishing depth and endurance. Far more than a simple mermaid, she is a complex cultural archetype born from the intimate and fraught relationship between an island people and the sea that surrounds them. Through her captivating beauty, her magical cap, and her tragic narratives of captivity and longing, the Merrow embodies the dual nature of the ocean as both life-giver and destroyer. She is a bridge to the Irish Otherworld, a relic of a mythological past preserved in the oral tradition, and a symbol co-opted by a nation forging its identity. Her enduring power lies in her ability to reflect timeless human concerns: the allure of the unknown, the pain of exile, the conflict between domestic duty and wild freedom, and the humbling recognition of forces in nature that far exceed human control. From the lips of 19th-century seanchaithe to the pages of modern poetry, the Merrow continues to sing her siren song, reminding us that the deepest waters are not those of the ocean, but those of the human heart, forever torn between the solid ground of home and the irresistible call of the deep.

Parsifal. Original artwork

Parsifal. Original artwork